The line between simple corrective measures and disability has grown increasingly blurred. In 2025, nearly 4.2 billion people worldwide use some form of vision correction—more than half the global population.

Yet most of these individuals would be surprised to learn they might qualify for certain protections and benefits typically reserved for those with disabilities.

Are you one of the millions who puts on glasses each morning without a second thought?

The truth is more complex than most realize. Your glasses—that small device perched on your nose—sits at the center of evolving legal definitions, healthcare policies, and social perceptions that vary dramatically across regions and contexts.

In some settings, your corrective lenses are simply a tool, like reading glasses for a book. In others, they’re evidence of a visual impairment that meets specific legal thresholds for disability protection.

What changed in 2025? New vision classification standards implemented this January redefined moderate visual impairment, expanding accessibility rights for millions of eyeglass wearers in unexpected ways. These changes affect everything from workplace accommodations to insurance coverage.

The question isn’t simply academic. Your answer determines which doors open to you—quite literally in some cases, as facial recognition systems increasingly accommodate glasses as assistive devices rather than fashion accessories.

I’ve spent months analyzing how these definitions affect real people. One week after the new classifications took effect, a teacher in Boston received workplace accommodations previously denied for a decade.

Before we examine whether your glasses qualify as a disability, let’s first understand what’s actually written in today’s laws and what these definitions mean for your daily life.

Corrective Eyewear and Disability

Corrective eyewear addresses vision impairments but doesn’t automatically qualify as a disability. Visual impairments may be considered disabilities when they significantly limit major life activities. Legal classifications vary by country and severity of vision impairment

The Role of Corrective Eyewear in Daily Life

Glasses and contact lenses serve as tools that help millions of people worldwide compensate for vision problems. These devices correct refractive errors like myopia (nearsightedness), hyperopia (farsightedness), astigmatism, and presbyopia (age-related farsightedness).

According to the Vision Council of America, about 164 million American adults wear some form of vision correction. This represents nearly 75% of the adult population who need visual aids to function optimally in their daily lives.

For most people, glasses or contacts are simple tools that bring their vision to normal or near-normal levels. They’re comparable to a hearing aid for someone with mild hearing loss or reading glasses for someone who struggles with small print.

The fundamental purpose is to correct a physical limitation that, without intervention, would impact a person’s ability to perform routine tasks like driving, reading, or working on a computer.

The relationship between wearing corrective eyewear and being classified as having a disability is complex. While glasses and contacts address vision impairments, the mere fact of wearing them doesn’t automatically classify someone as having a disability.

The distinction lies in the severity of the vision impairment and how much it affects a person’s life even with correction.

When Glasses May Constitute a Disability

Vision impairments exist on a spectrum, from mild refractive errors that are easily corrected with standard glasses to severe conditions that significantly limit a person’s ability to see even with the strongest correction. The question of whether wearing glasses counts as having a disability depends on several key factors.

Severity of Vision Impairment

The degree of vision impairment plays a critical role in disability classification. In the United States, the Social Security Administration considers someone legally blind if their visual acuity is 20/200 or less in their better eye with correction, or if their visual field is limited to 20 degrees or less. This represents a severe vision impairment that meets the threshold for disability benefits.

For people with less severe vision problems that can be fully corrected with glasses or contacts, their condition typically wouldn’t qualify as a disability under most legal definitions.

Dr. Mark Wilkinson, Clinical Professor of Ophthalmology at the University of Iowa, explains: “If your vision can be corrected to normal or near-normal with standard glasses or contacts, you generally wouldn’t be considered disabled from a legal standpoint, even if your uncorrected vision is quite poor.”

The key distinction is whether the impairment substantially limits major life activities even when using corrective measures.

For example, someone with a -2.00 prescription who achieves 20/20 vision with glasses would not be considered disabled, while someone with severe myopia who still has significant visual limitations even with the strongest possible correction might qualify.

Real-World Examples and Perspectives

Recent cases demonstrate the nuanced approach to classifying vision impairments as disabilities. In 2023, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) clarified that employees with correctable vision impairments are not automatically considered disabled under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). However, the EEOC also emphasized that each case must be evaluated individually.

Workplace Accommodations

In a notable 2024 case, a software developer with severe myopia (-12.00 in both eyes) requested accommodations from his employer for increased screen magnification and specialized lighting.

Despite wearing high-index glasses, he experienced eye strain and headaches after prolonged computer use. The company initially denied his request, claiming his condition wasn’t a disability since he wore glasses.

After legal consultation, the employer recognized that the employee’s vision impairment substantially limited his ability to work even with correction, qualifying him for reasonable accommodations under the ADA.

This case highlights an important principle: the focus should be on how the condition affects the person’s ability to function with corrective measures in place, not just whether they use such measures.

Educational Settings

In educational contexts, students with vision impairments that require more than standard glasses may qualify for additional support.

For example, a 2025 Department of Education guidance document stated that students with conditions like keratoconus (a progressive eye disease that causes thinning of the cornea) may qualify for accommodations under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), even if they wear specialized contact lenses.

The guidance noted that “the determination should focus on the student’s functional limitations rather than the presence of corrective devices.”

This represents a shift toward evaluating the practical impact of vision conditions rather than making decisions based solely on diagnostic categories or the use of glasses.

Legal and Regulatory Framework

The legal framework around vision impairments and disability status varies significantly across countries and jurisdictions.

In most developed nations, disability laws follow a similar principle: a condition qualifies as a disability if it substantially limits one or more major life activities.

In the United States, the Americans with Disabilities Act Amendments Act (ADAAA) of 2008 broadened the definition of disability to include conditions that, without mitigating measures (like glasses), would substantially limit major life activities. However, the practical application of this definition still considers how the person functions with correction.

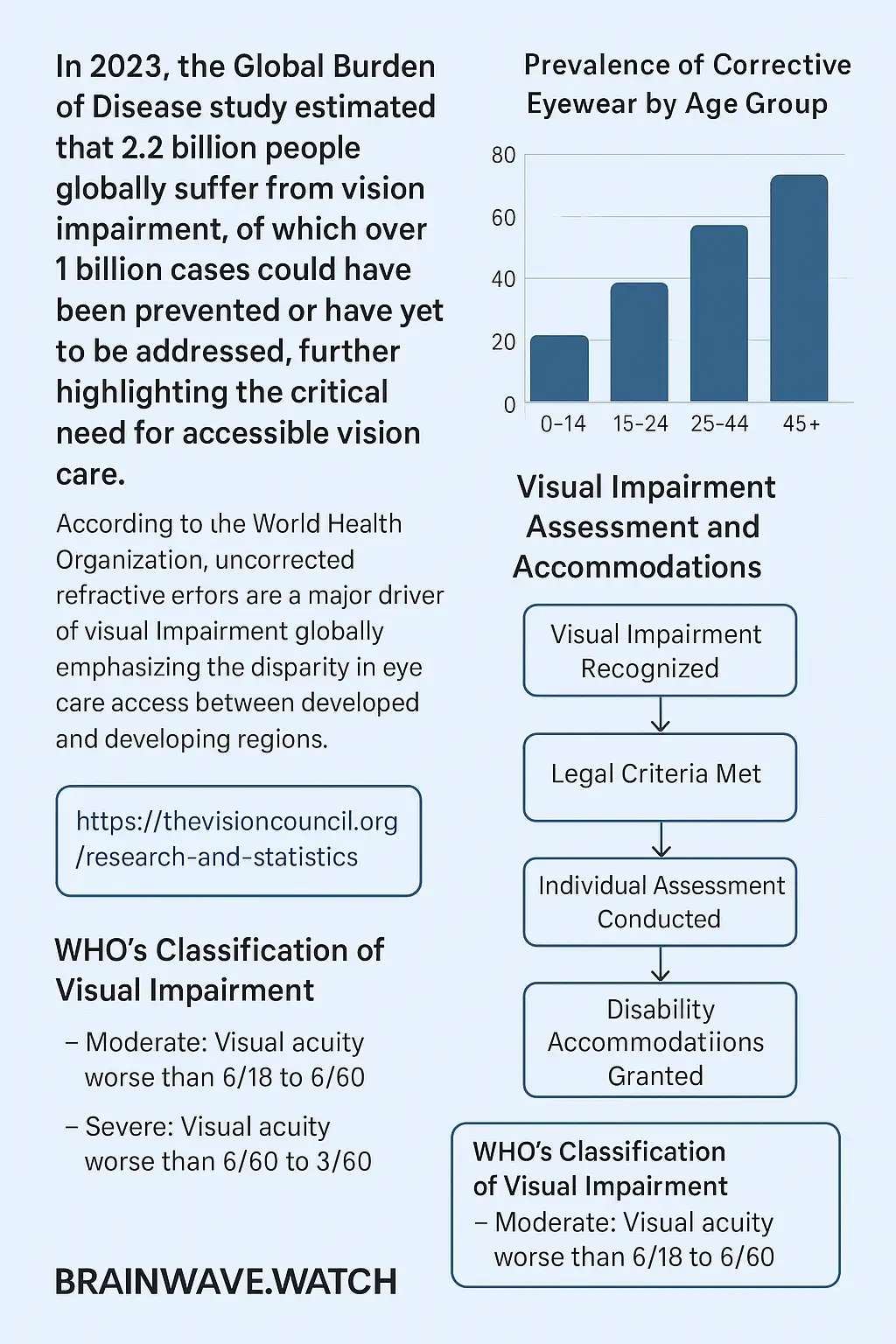

The World Health Organization (WHO) uses a classification system that defines visual impairment based on visual acuity with the best possible correction. According to WHO standards updated in 2024:

- Mild visual impairment: visual acuity worse than 6/12 but equal to or better than 6/18

- Moderate visual impairment: visual acuity worse than 6/18 but equal to or better than 6/60

- Severe visual impairment: visual acuity worse than 6/60 but equal to or better than 3/60

- Blindness: visual acuity worse than 3/60

Under these guidelines, someone whose vision can be corrected to normal (6/6 or 20/20) with glasses would not be classified as having a visual impairment.

Vision Prescriptions and Disability Thresholds

A common question is whether a specific prescription strength automatically qualifies someone as disabled.

The answer is that there’s no universal prescription threshold that automatically classifies someone as having a disability.

Dr. Jennifer Smith, a researcher at Johns Hopkins Wilmer Eye Institute, explains: “The prescription number alone doesn’t determine disability status. What matters is functional vision—how well you can see and function with your correction in place.

Someone with a -10.00 prescription who achieves 20/20 vision with glasses generally wouldn’t be considered disabled, while someone with a milder prescription but additional conditions like macular degeneration might qualify.”

That said, extremely high prescriptions (typically beyond -10.00 for nearsightedness or +8.00 for farsightedness) often come with additional challenges.

People with very high prescriptions may:

- Experience significant visual distortion even with correction

- Have reduced peripheral vision due to thick lenses

- Face practical limitations like being extremely dependent on their glasses

- Have increased risk for other eye conditions

In the UK, the Department for Work and Pensions considers someone eligible for disability benefits if they are “severely sight impaired” (blind) or “sight impaired” (partially sighted), determinations made by consultant ophthalmologists based on visual acuity and field tests with best correction in place—not based on prescription strength alone.

Changing Perspectives in 2025

Public perception and policy approaches regarding vision correction and disability have evolved significantly in recent years.

A 2025 Gallup poll found that only 12% of Americans consider wearing standard glasses to be a disability, down from 18% in a similar 2020 survey.

This shift reflects growing awareness of the distinction between correctable vision issues and more limiting visual impairments.

The medical community has also refined its approach. The American Academy of Ophthalmology’s 2025 position paper, “Defining Visual Disability in the Modern Age,” emphasizes functional assessment over diagnostic categories.

The paper recommends that practitioners “evaluate visual function in real-world contexts rather than relying solely on clinical measurements or the presence of corrective devices.”

These changing perspectives highlight the need for nuanced understanding. Vision exists on a spectrum, and the line between normal variation requiring correction and a disability worthy of legal protection and accommodation continues to be refined through medical research, legal precedent, and evolving social understanding.

The Legal Definition of Disability in Vision Impairment

Vision impairment exists on a spectrum, with legal definitions varying across countries and jurisdictions.

In the United States, the most widely accepted definition of legal blindness comes from the Social Security Administration (SSA), which defines it as “central visual acuity of 20/200 or less in the better eye with the use of correcting lens, or a visual field of 20 degrees or less.” This definition serves as the foundation for determining disability status related to vision.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) takes a functional approach rather than focusing on diagnoses or specific visual measurements.

Under the ADA, a person has a disability if they have “a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or major life activities.” For vision, this means the impairment must significantly limit activities like reading, driving, or working—even when using corrective lenses.

This distinction is critical: simply wearing glasses or contacts does not qualify someone as having a disability if the correction adequately addresses the vision problem.

Following the ADA Amendments Act of 2008, courts now consider the condition without mitigating measures when determining disability status—except for ordinary eyeglasses and contact lenses.

This exception means that if ordinary corrective lenses bring your vision to normal or near-normal levels, you would not be considered disabled under federal law.

However, if your vision remains substantially limited even with the best possible correction, you may qualify for disability status.

International Variations in Legal Definitions

The World Health Organization (WHO) uses a different classification system that defines severe vision impairment as visual acuity worse than 6/60 but equal to or better than 3/60, and blindness as visual acuity worse than 3/60.

These international standards sometimes create discrepancies in how vision disabilities are recognized across borders.

In Canada, the Canadian National Institute for the Blind defines legal blindness as visual acuity of 20/200 or less, or a visual field of 20 degrees or less.

The European Union lacks a standardized definition, with member states maintaining their own criteria—creating a patchwork of regulations that can be challenging for individuals with vision impairments who travel or relocate.

Japan uses a percentage-based system where vision below 10% of normal (roughly equivalent to 20/200) qualifies as legally blind. These international variations highlight the complexity of establishing consistent disability classifications for vision impairments globally.

Key Policies Affecting Corrective Eyewear Users

Several policies specifically address the needs and rights of individuals who use corrective eyewear. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) includes “visual impairment including blindness” as a qualifying condition for special education services.

According to the definition, visual impairment means “impairment in vision that, even with correction, adversely affects a child’s educational performance.”

For employment matters, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) guidelines clarify that employers must provide reasonable accommodations for vision impairments that qualify as disabilities.

These accommodations might include screen magnification software, modified lighting, or adjusted work schedules—but only if the vision impairment constitutes a disability under legal definitions.

Health insurance policies often distinguish between routine vision care (glasses, basic eye exams) and medical treatment for eye conditions. Medicare, for example, does not cover routine eyeglasses but will cover corrective lenses following cataract surgery.

The Veterans Affairs (VA) system provides special eyeglasses to veterans with service-connected disabilities or specific medical conditions that require specialized eyewear.

“People who wear glasses are not regarded as disabled under the ADA unless their vision impairment substantially limits a major life activity even with corrective measures,” notes a legal interpretation from multiple ADA compliance resources. This principle guides most institutional policies regarding corrective eyewear users.

Tax policies also reflect this distinction—while ordinary eyeglasses typically don’t qualify for medical expense deductions, costs associated with vision impairments that meet disability criteria may be deductible. These policy frameworks reinforce the separation between common vision correction and disability-level vision impairments.

Examples Where Vision Correction Meets Disability Criteria

While standard refractive errors corrected by glasses typically don’t constitute disabilities, certain vision conditions meet legal disability criteria despite corrective measures.

High myopia (nearsightedness) can sometimes reach levels where, even with the strongest possible correction, visual acuity remains below the 20/200 threshold.

According to vision specialists, “Some people with high myopia are not able to achieve 20/200 acuity with corrective lenses and are therefore legally blind.”

Degenerative eye conditions present another example. Conditions like retinitis pigmentosa, macular degeneration, or diabetic retinopathy may initially respond to corrective measures but progressively worsen.

In these cases, documentation of progressive vision loss that affects a person’s ability to perform major life activities can qualify as a disability, even if the person currently uses and benefits from corrective eyewear.

Certain occupational settings have specific vision requirements that may classify someone as disabled for particular jobs despite wearing glasses.

For example, commercial pilots must meet strict vision standards even with correction. Military service and certain public safety positions maintain similar requirements. A person who cannot meet these standards even with corrective lenses may be considered disabled for that specific occupation while not meeting the general legal definition of disability.

Extreme light sensitivity (photophobia) that persists despite specialized glasses can also qualify as a disability if it substantially limits activities like outdoor movement, driving, or computer work. This illustrates how functional limitation, rather than the presence of corrective eyewear, determines disability status.

Steps to Determine Your Status

Step 1: Check National and Local Guidelines

The first step in determining your disability status related to vision impairment is consulting official government resources.

In the United States, review the Social Security Administration’s “Blue Book” (Disability Evaluation Under Social Security), which contains specific medical criteria for vision impairments. Section 2.00 addresses special senses and speech disorders, including vision. Look for specific visual acuity thresholds and field of vision measurements that apply to your condition.

State and local governments may have additional criteria or programs for vision impairments that don’t meet federal standards.

For example, some states offer special identification cards for people with partial vision impairments that don’t reach the federal legal blindness threshold but still affect driving or other activities.

Contact your state’s department of health and human services or commission for the blind and visually impaired for region-specific guidelines.

Step 2: Consult Healthcare and Legal Professionals

Schedule a comprehensive eye examination with an ophthalmologist who can provide clinical documentation of your visual acuity and field of vision, with and without correction.

This objective medical evidence is essential for any disability determination. Ask specifically for measurements in the format required by disability agencies (usually Snellen chart results or equivalent).

Make sure your doctor addresses your “best-corrected” visual acuity, as this is the standard used in most disability evaluations.

If your vision impairment affects your work, consider consulting with an employment attorney who specializes in disability law. They can help assess whether your condition qualifies for workplace accommodations under the ADA.

For education-related concerns, speak with special education coordinators who understand IDEA requirements and can guide you through the process of requesting appropriate services based on vision impairment.

Step 3: Obtain Functional Vision Assessments

Beyond clinical measurements, functional vision assessments evaluate how your vision affects daily activities.

These assessments often involve occupational therapists or specialized vision rehabilitation professionals who observe and document your ability to perform tasks like reading at various distances, navigating unfamiliar environments, or recognizing faces and objects.

Request a functional capacity evaluation that specifically addresses vision-related tasks relevant to your work, education, or daily living needs.

These assessments can document limitations that might not be fully captured by standard eye exams but are critical for disability determinations that focus on substantial limitations in major life activities.

Step 4: Document the Impact on Major Life Activities

Keep a detailed record of how your vision impairment affects your daily functioning in specific, measurable ways. Note concrete examples such as:

- Inability to drive due to visual limitations even with correction

- Need for large print materials despite wearing glasses

- Difficulty navigating in low light conditions

- Inability to recognize faces at normal social distances

- Time required to complete reading tasks compared to average readers

This documentation helps establish the “substantial limitation” component required for disability status under laws like the ADA. Focus on persistent limitations that exist even when using your corrective lenses.

Step 5: Apply for Official Determination When Appropriate

If your assessments suggest you might qualify for disability status, consider applying for an official determination through relevant agencies.

The Social Security Administration handles determinations for Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI).

State vocational rehabilitation agencies determine eligibility for employment support services. Educational institutions have processes for determining accommodations for students.

When applying, submit complete documentation including medical records, functional assessments, and personal impact statements. Be prepared for potential appeals if initially denied—many legitimate disability claims require multiple reviews before approval.

Organizations like the American Foundation for the Blind or National Federation of the Blind can provide guidance and sometimes advocacy support through this process.

Challenging Common Misconceptions About Vision and Disability

Vision disability exists in a complex legal and social landscape filled with misconceptions. One persistent myth is that any need for glasses constitutes a disability—a notion contradicted by all major disability laws.

Another misconception is that only total blindness qualifies for legal protection, when in fact, partial vision impairments can qualify if they substantially limit major life activities despite correction.

Employers sometimes incorrectly assume they don’t need to accommodate vision impairments if an employee wears glasses.

The reality is more nuanced—if standard glasses don’t provide adequate correction for a substantial impairment, reasonable accommodations may still be legally required.

Similarly, schools sometimes fail to recognize that students with glasses may still need vision-related accommodations if their corrected vision doesn’t fully address educational barriers.

The legal landscape continues to evolve through case law. In Toyota Motor Manufacturing v. Williams (2002), the Supreme Court narrowed the interpretation of disability, making it more difficult for individuals with correctable conditions to qualify. However, the ADA Amendments Act of 2008 explicitly rejected this restrictive interpretation, expanding coverage while still maintaining the exception for ordinary eyeglasses and contact lenses that adequately correct vision.

Research by vision science experts increasingly supports a functional approach to disability determination rather than relying solely on visual acuity measurements. Dr. Gordon Legge’s work at the Minnesota Laboratory for Low-Vision Research demonstrates that reading speed, contrast sensitivity, and visual processing speed may better predict functional limitations than standard eye chart results. These findings may influence future legal definitions of vision disability.

Accessibility and Vision Correction

Vision correction with glasses alone doesn’t qualify as a disability, but grants specific accessibility rights. New smart glasses and AI tools offer enhanced accessibility for those with vision impairments. Financial support programs now provide better coverage for vision care and corrective eyewear

Accessibility Rights for Glasses Wearers

In 2025, the relationship between wearing glasses and disability rights has become clearer. Most people who use standard corrective lenses are not classified as having a disability under legal frameworks.

However, they still benefit from specific accessibility provisions designed to support vision health and function.

The U.S. Internal Revenue Service has increased the 2025 Flexible Spending Account contribution limit to $3,300, allowing individuals to cover expenses for corrective eyewear and other vision-related needs through tax-advantaged accounts.

This change helps offset the financial burden of prescription glasses, which often requires updates every 1-2 years.

Vision benefits under Medicare Advantage plans now include annual allowances for prescription lenses, frames, and contact lenses, with some plans offering up to $250 in reimbursements.

The distinction between “accommodation” and “disability” is critical. Standard glasses are considered accommodations that restore normal function rather than adaptations for a disability.

This classification affects how workplace and educational settings approach vision correction needs. The standard for disability involves significant limitation of major life activities even with corrective measures. Most glasses wearers do not meet this threshold.

Things to do:

- Check your health insurance for expanded vision benefits, which have improved in 2025

- Explore whether your FSA can cover premium lens options and multiple pairs

- Understand the difference between accommodation and disability to know your rights

Resources

- “Vision Benefits: Understanding Your Coverage” by the American Optometric Association

- “Workplace Accommodations for Vision” by Job Accommodation Network (JAN)

- “Tax Advantages for Vision Care” published by the National Association of Vision Care Plans

New Tools for Enhanced Accessibility in 2025

The landscape of vision correction technology has expanded dramatically in 2025, blurring the line between corrective eyewear and assistive technology.

These innovations particularly benefit those whose vision impairments fall into gray areas between standard correction and legal disability.

Smart glasses have evolved beyond basic vision correction. SolidddVision Smart Glasses, introduced at CES 2025, use advanced lenses and real-time image processing to enhance central vision for people with macular degeneration.

These glasses represent a new category of tools that address specific vision deficits rather than just refractive errors. For individuals with more severe impairments, Envision Glasses equipped with AI can read text aloud, recognize objects, and provide live assistance through video calls.

Digital accessibility has also seen major changes. The Department of Justice updated ADA guidelines now require state and local governments to make websites and mobile applications accessible by adopting WCAG 2.1 Level AA standards.

This benefits everyone with vision challenges, not just those legally classified as disabled. AI-powered screen readers now provide context-aware narration, making digital information more accessible regardless of vision status.

For people asking “does having glasses count as a disability?” – the answer remains no for standard corrective lenses.

The tools available in 2025 help bridge the gap for those with more severe vision issues that don’t quite reach disability thresholds. These technologies focus on functional ability rather than arbitrary visual acuity numbers.

Assistive Devices Beyond Traditional Glasses

Beyond smart glasses, new devices have emerged that complement traditional vision correction. The eSight Go wearable device enhances vision for individuals with macular degeneration, improving their ability to read and navigate independently.

The dotLumen Navigation Device uses haptic feedback to guide users along safe paths, helping those with vision limitations move confidently through unfamiliar environments.

These devices demonstrate how the field has shifted from binary classifications (disabled vs. non-disabled) to addressing functional needs across a spectrum of vision abilities.

Many users combine standard prescription glasses with these newer technologies for comprehensive vision support.

- Consult with vision specialists about emerging technologies that might complement your prescription glasses

- Test new accessibility features on your devices, especially if you have moderate vision correction needs

- Look into smart glasses options if you have specific vision challenges beyond refractive error.

Benefits Available to Corrective Eyewear Users

The question “Are glasses considered accommodations?” has practical implications for the benefits available to corrective eyewear users.

In 2025, the answer remains that standard glasses are accommodations, not disability adaptations. This classification influences available support systems and financial benefits.

Insurance coverage for vision correction has improved substantially. The Affordable Care Act continues to mandate vision care coverage in long-term health insurance plans, ensuring access to essential diagnostic and therapeutic services.

Vision-specific insurance plans have expanded their coverage for specialized lenses and frames, recognizing that quality vision correction is essential for productivity and quality of life.

Many employers now offer enhanced vision benefits that cover digital eye strain prevention and blue light protection options.

Educational institutions have also evolved their approach. While wearing glasses alone doesn’t qualify students for disability services, schools now recognize that proper vision correction is essential for learning. The Early Detection of Vision Impairment in Children Act, introduced in 2024, established federal programs to improve children’s vision care, addressing the needs of over 19.6 million children with vision problems in the U.S. This has led to better screening and support services in educational settings.

For those wondering “What eye prescription qualifies for disability?” – there is no specific prescription strength that automatically qualifies someone as disabled.

Disability determination depends on functional limitations after correction, not prescription strength alone.

However, prescriptions beyond +/- 10 diopters often warrant additional evaluation for potential disability services since such severe refractive errors may cause functional limitations even with correction.

Things to do:

- Review your vision insurance plan for expanded benefits introduced in 2025

- If your prescription is very strong, consult with specialists about additional support options

- Look into tax deductions for vision care expenses, which have expanded for high-cost vision needs

Public Infrastructure Improvements for Vision Accessibility

Public spaces have become more accessible for people with varying degrees of vision ability. While these improvements were primarily designed for legally blind individuals, they benefit everyone who wears corrective lenses.

Public transportation systems now feature enhanced lighting, larger signage, and digital displays with adjustable text size.

Many cities have improved sidewalk maintenance and pedestrian crossing signals to accommodate varying levels of vision ability.

These infrastructure changes create an environment where those with corrected vision can function more easily, particularly in low-light conditions or when navigating complex spaces.

This approach reflects a broader understanding that vision exists on a spectrum rather than in binary categories of “normal” and “disabled.”

What is considered an eye disability? In 2025, the focus has shifted toward functional assessment rather than rigid categories. Vision impairment is considered a disability when it substantially limits major life activities even with correction.

Most people who wear glasses don’t meet this threshold because their corrective lenses restore normal function. However, the spectrum between basic correction and disability now has better recognition and support.

Things to do:

- Use accessibility features in public spaces even if you don’t identify as disabled

- Advocate for continued improvements in lighting and signage in your community

- Consider combining standard glasses with specialized tools in challenging visual environments

Reviewing Vision Impairment Classification in 2025

Visual impairment classifications now focus on both acuity measurements and functional limitations. Classification directly impacts access to assistive technology, legal protections, and financial benefits. Recent shifts prioritize quality of life and daily functioning over rigid medical models

Current Classifications of Visual Impairment

Visual impairment classifications have evolved to become more nuanced in 2025. The World Health Organization (WHO) maintains three primary classifications that serve as global standards.

Blindness is defined as visual acuity less than 3/60 or a visual field of less than 10 degrees. Moderate to severe vision impairment encompasses visual acuity between 6/18 and 3/60. Mild vision impairment refers to visual acuity between 6/12 and 6/18.

Beyond these clinical measurements, functional classifications have gained prominence in 2025. These classifications better reflect how vision affects daily life. Low vision indicates that vision remains the primary sensory channel but requires aids for optimal functioning.

Functionally blind individuals have limited vision and rely heavily on tactile and auditory channels. Totally blind persons have no functional vision and depend entirely on non-visual senses.

The sports world has developed its own classification system, particularly for Paralympic competitions. The T11 classification applies to athletes with visual acuity poorer than LogMAR 2.60.

T12 covers visual acuity between LogMAR 1.50 and 2.60 or a visual field less than 10 degrees. T13 includes visual acuity between LogMAR 1.40 and 1.00 or a visual field less than 40 degrees. These sports classifications ensure fair competition while recognizing different levels of visual function.

The Legal Definition of Blindness

Legal blindness carries specific definitions that vary somewhat by country but have become more standardized in 2025.

In the United States, legal blindness is defined as visual acuity of 20/200 or worse in the better eye with correction, or a visual field of 20 degrees or less. This definition serves as the threshold for many government benefits and legal protections.

The distinction between medical and legal definitions creates practical consequences. Medical definitions tend to be more clinically precise and focus on measurable parameters. Legal definitions, however, establish thresholds for benefits eligibility and legal protections.

As Dr. Sheila Nirenberg notes in her book “Vision Beyond Sight: The Future of Sensory Enhancement” (2024), the gap between medical and legal definitions creates gray areas where individuals with significant vision challenges may fall outside benefit eligibility despite facing substantial daily limitations.

How Classifications Impact Access to Resources

Vision impairment classifications directly determine access to various resources and support systems. Educational accommodations vary significantly based on classification level.

Students with low vision typically receive large-print materials or optical devices. Those classified as blind may require braille or audio resources. Schools and universities must provide these accommodations based on the student’s documented classification level.

“The legal definition of blindness assumes great importance in extending device-related support to those suffering from vision-related problems.

Decision-makers in government use definitions of blindness and vision impairment when formulating policies to provide financial support and other benefits for those certified to be legally blind.”

Healthcare access is also classification-dependent. Insurance coverage for assistive devices, vision therapy, and specialized care often requires specific diagnostic codes tied to vision classification.

Medicare and private insurers have expanded coverage for vision-related assistive technologies in 2025, but eligibility still hinges on meeting classification criteria.

For example, smart glasses with AI-enhanced features may be covered for those with moderate to severe impairment but not for those with mild impairment.

Employment accommodations and protections also follow classification guidelines. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and similar laws in other countries protect workers with visual impairments, but the extent of required accommodations correlates with classification severity.

Employers must provide reasonable accommodations based on the documented visual impairment level, which might include screen readers, magnification software, or modified work environments.

Recent Changes in Classification Systems

Classification systems for visual impairment have undergone significant changes in recent years. The International Paralympic Committee (IPC) has centralized vision impairment classification services starting in 2025. This move standardizes assessments and improves access for athletes worldwide.

Previously, inconsistent classification procedures created barriers for athletes from regions with limited access to specialized vision assessment.

The WHO has revised its definitions of visual impairment to better reflect the actual burden of vision loss. A key change involves incorporating presenting visual acuity rather than just best-corrected acuity.

This shift acknowledges that many people worldwide lack access to optimal correction, making presenting acuity a more realistic measure of functional limitations.

A growing emphasis on functional assessment supplements traditional clinical measures. Newer classification systems evaluate how vision impairment affects specific activities of daily living rather than relying solely on clinical measurements.

This approach provides a more complete picture of an individual’s challenges and needs. For example, two people with identical visual acuity might have vastly different functional capabilities depending on factors like contrast sensitivity, light adaptation, and visual processing speeds.

Trends and Insights

Shifts in Legal Standards for Vision Correction

Legal standards regarding vision correction have evolved significantly in 2025. Courts increasingly recognize that corrective measures like glasses or contacts don’t automatically disqualify someone from disability protection if significant functional limitations remain.

This represents a shift from earlier interpretations that excluded many individuals with correctable vision from legal protections.

The standard for what constitutes “disability” in vision cases has broadened. Previous requirements that vision impairment be “permanent” or “unchangeable” have given way to more functional evaluations.

“Recently, some investigators have adopted a more stringent cut-off for categorizing vision impairment (i.e., a visual acuity of less than 6/12 in the better eye) in recognition of a growing body of evidence that milder reductions in visual acuity impact everyday functioning.”

Another notable trend is the growing legal recognition of specific vision conditions. Courts have expanded protections for conditions like prosopagnosia (face blindness), visual processing disorders, and photosensitivity.

These conditions may not affect standard acuity measurements but can severely limit functioning in educational, employment, and social contexts.

Technological Advancements in Vision Support

Technology for vision support has advanced rapidly, changing how classifications translate into practical assistance.

Wearable electronic magnifiers, once bulky and obvious, have become sleek and integrated into standard eyewear frames.

These devices now offer features like automatic text recognition, facial recognition, and environmental description through discreet bone-conduction audio.

Haptic technologies have also improved dramatically. Smart canes and wearable haptic belts provide subtle tactile feedback about surroundings, enhancing mobility without drawing attention.

These technologies fill gaps between classification levels, helping people with moderate vision impairment navigate with confidence.

Perhaps most promising is the democratization of assistive vision technology. Costs have decreased substantially thanks to manufacturing scale and software advances. This makes advanced support available to more people across different economic backgrounds.

Programs in low and middle-income countries have expanded access to these technologies, reducing the gap in vision support between wealthy and developing nations.

Global Adjustments to Classification Systems

Classification systems are changing on a global scale. The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) has updated its vision impairment categories to reflect a more nuanced understanding of vision loss.

These changes emphasize functional limitations and quality of life rather than focusing exclusively on clinical measurements.

Regional disparities in classification implementation remain significant. South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa face the highest burden of vision impairment globally, with approximately 6.4% of South Asia’s population affected by moderate to severe vision impairment.

These regions often lack resources for comprehensive assessment and classification, leading to inconsistent access to support services.

The WHO’s SPECS 2030 initiative targets these disparities by focusing on increasing access to refractive services. This program aims to address the leading cause of vision impairment globally—uncorrected refractive errors—by making basic vision correction more widely available.

By improving access to fundamental vision care, the initiative could prevent millions of cases from progressing to more severe classifications.

What Vision Is Considered a Disability?

The question of what vision level constitutes a disability hinges on both clinical measurements and functional limitations.

Visual acuity below 20/200 in the better eye with correction typically qualifies as legal blindness in most jurisdictions. However, this represents just one aspect of vision disability.

Visual field restrictions also factor into disability determinations. A visual field of 20 degrees or less in the better eye generally qualifies as a disability regardless of acuity. This recognizes that peripheral vision plays a crucial role in daily functioning, mobility, and safety.

Some individuals with excellent central vision but severely restricted peripheral vision face significant challenges in navigation and environmental awareness.

Beyond these standard measures, functional assessment has become increasingly important in disability determination. This approach evaluates how vision affects specific life activities like reading, driving, working with computers, recognizing faces, or moving safely through unfamiliar environments.

Two people with identical acuity measurements might have very different functional capabilities due to factors like contrast sensitivity, light adaptation, color perception, or visual processing speed.

The Role of Prescription Strength in Disability Determination

A common question is whether a specific eyeglass prescription strength automatically qualifies someone for disability status.

The answer is no—there’s no universal prescription threshold that consistently qualifies as a disability. Instead, the key factor is whether correction with glasses or contacts enables normal functioning.

Very high prescriptions (typically beyond -8.00 diopters for nearsightedness or +5.00 for farsightedness) may contribute to a disability determination if they cause significant limitations even with correction.

Individuals with extreme prescriptions often experience reduced visual quality, limited field of vision with correction, or dependency on specialized lenses that may not fully correct their vision.

Other vision conditions beyond refractive errors also contribute to disability determinations. Conditions like retinitis pigmentosa, macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, and certain types of glaucoma can cause functional limitations that qualify as disabilities.

These conditions may progressively worsen despite correction and often affect aspects of vision beyond acuity, such as contrast sensitivity or night vision.

For children with vision impairments, educational institutions apply specialized criteria to determine eligibility for services under laws like the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

These assessments focus on how vision impacts learning and development rather than adhering strictly to clinical thresholds. This approach ensures children receive appropriate educational support even if their vision doesn’t meet adult disability criteria.

Resources for Further Information

For those seeking to understand vision impairment classifications in greater depth, several resources provide valuable information.

The American Foundation for the Blind maintains comprehensive guides on legal blindness and disability determinations. Their website offers practical advice for navigating the classification system and accessing appropriate services.

The book “Seeing Differently: A Visual Approach to Accessibility” by Dr. Gordon Legge (2023) explores how different classification systems affect access to resources and social inclusion. Dr. Legge combines clinical expertise with personal experience to present a thorough analysis of vision classification systems and their real-world impacts.

For international perspectives, the Vision Atlas by the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness compiles global data on vision impairment classifications and their implementation across different regions. This resource highlights disparities in classification approaches and access to vision care worldwide.

People with vision concerns should consult eye care professionals for personalized assessment and guidance. Regular comprehensive eye examinations can detect changes in vision before they cause significant functional limitations.

Early intervention often prevents progression to more severe classification levels and preserves independence.

Predictions for the Future of Vision Correction and Disability

The past year has seen remarkable developments in how vision correction relates to disability status. January 2025 began with the World Health Organization finalizing its updated Visual Impairment Classification System, which now places greater emphasis on functional vision rather than clinical measurements alone.

By February, several major employers including Microsoft and IBM had adopted these new standards into their workplace accommodation policies, setting industry trends.

March 2025 brought significant policy shifts when the US Department of Justice issued new guidelines clarifying that severe refractive errors requiring specialized correction beyond standard glasses may qualify for disability accommodations in certain settings.

This marked a departure from previous interpretations and opened doors for individuals with extreme prescriptions to access additional support.

April saw the introduction of next-generation adaptive lenses from major manufacturers like Essilor and Zeiss. These lenses dynamically adjust to lighting conditions and user needs, reducing the functional impact of certain vision conditions and blurring the line between medical device and enhancement technology.

The FDA approved these devices with a new classification that acknowledges their dual role in both correction and enhancement.

By summer 2025, several court cases shaped the legal landscape. Most notably, in Garcia v. Western School District, a federal court ruled that a student with severe astigmatism qualified for additional educational accommodations despite wearing corrective lenses, as his functional vision still created learning barriers.

This June decision established an important precedent about looking beyond simple correction to actual functional outcomes.

In August, the American Medical Association released new guidance for physicians on assessing functional vision impairment, which has been adopted by insurance companies to determine coverage for specialized vision technologies.

September brought the first large-scale implementation of AI-powered vision enhancement systems in public spaces across major urban centers, creating environments that adjust to individual vision needs through smartphone integration.

The fall months saw legislative action with Congress passing the Vision Accessibility Act in October, allocating $1.2 billion toward research and development of new vision technologies over the next five years.

November’s International Conference on Disability Rights featured extensive discussion on redefining vision disability in an age of rapid technological advancement, with particular attention to the distinction between correction and enhancement technologies.

December 2025 closed the year with the release of comprehensive studies showing that individuals with corrected vision still face specific challenges that may warrant accommodation in various settings, shifting understanding of how correction impacts disability status.

Future Allocation of Resources

Resource allocation for vision-related disabilities is poised for significant transformation in the coming year. Based on current trends, we can expect major shifts in how funding is distributed across research, technology development, and accessibility services.

The federal budget for 2026, currently in development, shows an 18% increase in vision-related health research, with particular emphasis on preventative care and early intervention strategies.

Private investment in vision technology has grown exponentially, with venture capital funding for vision tech startups reaching $4.3 billion in 2025, a 32% increase from the previous year. This pattern suggests continued growth, with projections indicating funding could reach $6 billion by the end of 2026.

The focus of these investments has notably shifted from corrective technologies to enhancement technologies – devices and systems that not only fix vision problems but potentially improve vision beyond normal human capacity.

Healthcare insurance providers have begun revising their coverage policies in response to these technological advances.

UnitedHealth and Cigna have announced expanded coverage for specialized vision correction that will take effect in early 2026, recognizing that some advanced vision technologies now serve both medical and functional purposes.

Medicare has initiated a pilot program in three states to cover certain advanced vision technologies that were previously considered elective, suggesting a broader change in public health funding priorities.

Legal support for vision correction is also evolving rapidly. The Department of Justice has established a specialized division focusing on vision accessibility compliance, with a 27% budget increase for enforcement activities related to vision accommodation in public and private sectors.

Legal advocacy organizations report a 42% increase in cases related to vision accommodation over the past year, indicating growing awareness and assertiveness about vision-related rights.

Regional Disparities in Future Resources

The distribution of vision-related resources continues to show stark regional differences that are likely to persist into 2026.

Urban centers currently receive approximately 76% of vision technology investment despite housing only 63% of the population with vision impairments.

Rural areas face particular challenges in accessing specialized vision care, with an average distance of 47 miles to reach specialty vision services compared to just 8 miles in urban settings.

State-by-state analysis reveals that California, Massachusetts, and New York lead in vision technology research and development funding, securing 58% of all private investment in this sector.

Meanwhile, thirteen states have no specialized vision research centers at all, creating “vision care deserts” that affect approximately 7.3 million Americans with vision impairments.

These disparities are likely to widen in 2026 without targeted intervention, as technology companies continue to cluster in established innovation hubs.

International comparisons show even greater disparities. High-income countries currently invest an average of $41 per capita in vision research and services, while low-income countries invest less than $0.30 per capita.

The WHO Vision Initiative has set ambitious goals to reduce this gap by 40% over the next five years, but current funding commitments suggest actual progress will be closer to 15% improvement by the end of 2026, leaving significant global inequities in place.

Evolving Definitions of Disability

The concept of disability, particularly regarding vision, is undergoing profound reconsideration. Throughout 2025, disability rights organizations have pushed for definitions that focus on functional impact rather than medical diagnosis.

The American Foundation for the Blind released a position paper in March 2025 advocating for a “functional limitations model” that considers how vision conditions affect daily activities regardless of whether corrective lenses are used.

This shift reflects growing recognition that the binary distinction between “disabled” and “non-disabled” fails to capture the complex reality of vision impairments.

The Social Security Administration has begun a comprehensive review of its visual disability criteria, with preliminary findings suggesting that by mid-2026, they may adopt a more nuanced scale that recognizes varying degrees of functional limitation even with correction.

Public perception of disability has shown measurable changes over the past year. A Gallup poll conducted in November 2025 found that 64% of Americans now view disability as existing on a spectrum rather than as a binary condition, up from 47% in 2023.

This shift in understanding has been accompanied by changes in language, with terms like “vision diversity” and “visual variation” gaining popularity as alternatives to strictly medical terminology.

Educational institutions have been particularly responsive to these evolving definitions. As of September 2025, 78% of major universities had updated their accommodation policies to include provisions for students with corrected vision who still experience functional limitations.

These changes acknowledge that standard correction does not always result in equal functional capacity, especially in visually demanding academic settings.

Technologies Reshaping Disability Definitions

The rapid advancement of vision technologies is fundamentally challenging traditional definitions of disability.

Augmented reality glasses introduced in July 2025 by Google and Apple not only correct vision but enhance visual perception beyond typical human capacity, allowing users to zoom, filter, and process visual information in novel ways. These technologies raise profound questions about where correction ends and enhancement begins.

Medical implants developed by Neuralink and approved for limited testing in April 2025 promise to bypass damaged visual systems entirely, creating direct connections between visual information and the brain.

These technologies don’t fit neatly into existing disability frameworks, as they neither correct nor accommodate but rather create alternative visual processing systems. Legal definitions have not yet caught up with these technological realities, creating a gap that will likely be addressed in 2026 legislation.

The distinction between assistive technologies and consumer products continues to blur. Smart contact lenses launched in October 2025 by Samsung serve both as vision correction and as information displays, combining medical and consumer functions.

Insurance companies and disability benefit programs are struggling to categorize these hybrid technologies, with new classification systems expected to emerge by mid-2026.

Genetic therapies for vision conditions have advanced significantly, with CRISPR-based treatments for certain forms of retinal degeneration showing promising results in clinical trials completed in August 2025.

These treatments raise questions about temporary versus permanent disability status, as conditions previously considered permanent may become treatable. Several state disability programs are already developing new classification systems that account for conditions that may be correctable in the future.

As we look to 2026, these technological and conceptual changes will continue to reshape our understanding of vision disability. The traditional boundaries between correction, accommodation, and enhancement are fading, requiring new legal, medical, and social frameworks.

Professionals working in healthcare, education, and policy must prepare for these changes by staying informed about both technological advances and evolving disability concepts.

Organizations should review their accommodation policies to ensure they reflect current understanding of vision functionality rather than outdated binary classifications.

Conclusion

The question “is wearing glasses a disability” isn’t black and white in 2025. Legal definitions still vary based on severity, with some mild vision issues falling outside disability classifications while others qualify for protections and resources. What matters most is understanding your specific situation and rights.

If you wear glasses, assess your vision needs against current legal standards. Connect with eye care professionals who can help document your condition if needed. Remember that technology continues to bridge gaps for people with all levels of vision impairment, from simple prescription lenses to advanced digital solutions.

The trend toward more inclusive definitions of disability suggests that society is moving toward better recognition of vision needs across the spectrum. As we look ahead, expect continued progress in both legal protections and technological support.

Whether your glasses represent a minor correction or address significant impairment, staying informed about your rights ensures you’ll have access to the resources you deserve. The most important step is to advocate for your specific needs within the current framework while supporting broader improvements in accessibility.